In my career as a foreign correspondent, I have witnessed the strange psychology of the mob in many conflict zones. I have observed at close range how a mob forms. How a mob can so quickly resort to violence. And how that violence can so easily result in a death or serious injury. I was born and raised in a country that endured a decades-old war so I knew mobs before I began reporting on them.

But I wasn’t prepared for when a Twitter mob came for me.

Let me explain. For the last nine years I have reported on and researched a country I watched slowly tip into civil war. Every conflict since time immemorial has also been a propaganda war, its protagonists locked in a fierce battle for narrative. Today, in an era of “fake news” when anyone can become a keyboard warrior through social media, the stakes are even higher.

The country I report on – though access is increasingly difficult – is awash with not just misinformation, but disinformation willfully spread by the belligerents and their supporters. They want to confuse the population of that country but also the outside world about what exactly is going on there. Not surprisingly, they see journalists like me, whose job it is to unpick those narratives and report the realities of the conflict and the impact on civilians, as a threat.

And so, the mob came for me. It began, as mobs in real life begin, with just a few individuals. Shrill, partisan voices – some of them hiding behind anonymous Twitter handles – whose baiting and baying drew the attention of others until quite a virtual crowd had gathered. The accusations of that initial handful were designed to make some noise that would attract a wider audience: I was in the pay of this faction or the other in what was then a rapidly spiraling conflict; I was a liar; I was a propagandist; I was a spy. Their smears travelled fast – and far. The accusations against me were shared on other social media, including Facebook forums, and eventually ended up broadcast on TV channels allied with particular actors in the conflict.

Who took part in the mob? Most were citizens of the country I work on. Some lived there, others were part of a diaspora scattered across the Middle East, Europe, the US and Canada. But others were not from that country, instead they were linked to it through personal connections – some business related – or by a certain type of social media activism that draws both the bored and those desperate for a cause. Most were men, of all ages.

But a not-insignificant number were women. The women tended to be foreigners whose reasons for being interested – sometimes obsessively so – in the country I work on were not clear. The archetypal keyboard warriors sitting comfortably far away from a conflict zone whose tweets had serious consequences for me as a journalist on the ground.

I grew up on the schoolyard maxim that ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me’ and I have the thick skin of an experienced reporter, particularly one who has covered numerous conflicts in different parts of the world. But over the past decade, I have also seen several colleagues – including dear friends – kidnapped, tortured or killed, some in the most brutal ways by so-called Islamic State. I know how dangerous it can be for rumours to spread that a journalist is a spy, I know where such rumours can sometimes lead. Abduction, detention, torture, and worse. I have been detained by belligerents and security forces in several countries. My fears are real.

Much of what I was subjected to on social media was gender-based. The country I work in is socially conservative and many of the worst male trolls hid behind anonymous accounts. Their attacks were often sexually explicit and sometimes included insinuations about my personal life or comments about my appearance. Some drew derogatory cartoons of me which they posted on social media. Several men sent me threats – often of a sexual nature – in personal messages and emails, some didn’t even bother to hide their identity. On one occasion, I froze when I realized a man I had just been introduced to, along with his wife, at a public event was one of the most persistent trolls

I was also struck by how often women encouraged the men in their aggressive trolling of me. They cheered the misogyny and took glee even in the sexually explicit attacks I was subjected to. Particularly disturbing was to see how some women even mocked those who had defended me and publicly raised concerns about my safety as the attacks continued.

At times it felt like swarms of trolls around me. Their harassment online but also the fact their smears were taking root beyond social media and putting my safety at risk caused me considerable stress.

Everyone has a different way of dealing with such harassment. I’m a believer in not feeding the trolls. And while I initially resisted blocking people on Twitter – preferring to mute instead – now I have learned to love the blocking button. For some of those who had trolled me for years, it appeared to be a case of out of sight, out of mind.

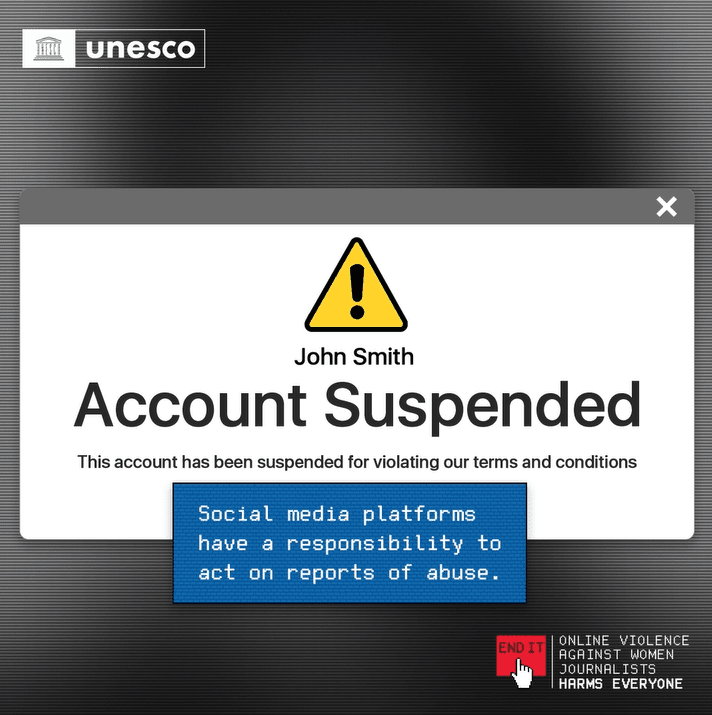

My attempts to report accounts to Twitter were largely in vain. Even someone who openly discussed whether it was better if I were killed or not was judged not to be in violation of what Twitter calls its community standards. This is not good enough. These are dangerous days for journalists across the world. We are being targeted in greater numbers than at any other period in my lifetime. We are being harassed, threatened, jailed. Some of us have been tortured, even murdered. All too often it begins with a virtual mob and ends with terrible consequences in real life. I have not been detained or physically attacked as a result of the baseless accusations against me that began on social media. But given those smears have now been amplified far beyond Twitter, they pose a risk to my personal safety and security. As a result, I have had to restrict my movements in the country I focus on. I take few chances. My work suffers as a result.

Companies like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube should do more to address the ways their platforms are used to harass, defame and incite. Because, right now, the mob is coming for far too many of us.